I came across this piece Bên vỉa hè Sài Gòn in the Chiêu Dương (Sunrise) newspaper, a Vietnamese newspaper in Sydney Australia, on the eve of April 30 — a date many Vietnamese living in the diaspora refer to as Tháng Tư Đen (Black April), marking the fall of Saigon. This piece captures the sentiment of many Vietnamese living overseas often echoed in newspapers, memoirs, or cultural affects – essence of life in Saigon, both before and after that turning point. The author is Thanh Saigon. In translating the work, I’ve tried to preserve its nostalgic tone and the distinct style of Vietnamese writing, with its attentive gaze on the rhythms of ordinary life.

Lý Lan’s piece “Dân ngã tư (People of the Intersections)” offers a quiet, profound meditation on the lives of the working class in Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn—lives that are simple, yet full of quiet resilience. These are people who rarely complain, even as they navigate the unrelenting demands of survival in a city that has never stopped changing.

Since 1975, Sài Gòn has evolved like any city does. But much of its daily rhythm remains familiar. The stories Lý Lan captures continue to echo deeply, especially for those of us now living far away, carrying these memories as part of who we are.

A friend of mine told me of a story of a humble coffee cart near a T-junction that leads to the market near Xóm Củi. Owned by an old man, it’s just a small cart covered by a bright tarp—easily packed away and pushed home after a long day serving simple coffee to local workers.

The old man’s house is close by, yet his cart never leaves the street. It feels as though it has always been there. At dawn, one can hear the soft sounds of morning: the tarp being pulled open, the crack of wood being split to start the fire.

And then comes the smell of coffee—drifting in the stillness of the early morning. Soon after, quiet conversations begin with early customers, murmurs about life’s necessities: whether it will rain or shine, and how the day might unfold. They wait, not just for coffee, but for company.

Rain or shine—these things belong to nature. These coffee customers didn’t need gadgets for scientific forecasts. They speak of the weather like a doctor might speak of a medical condition. Whether their predictions are right doesn’t matter. What matters is the exchange itself.

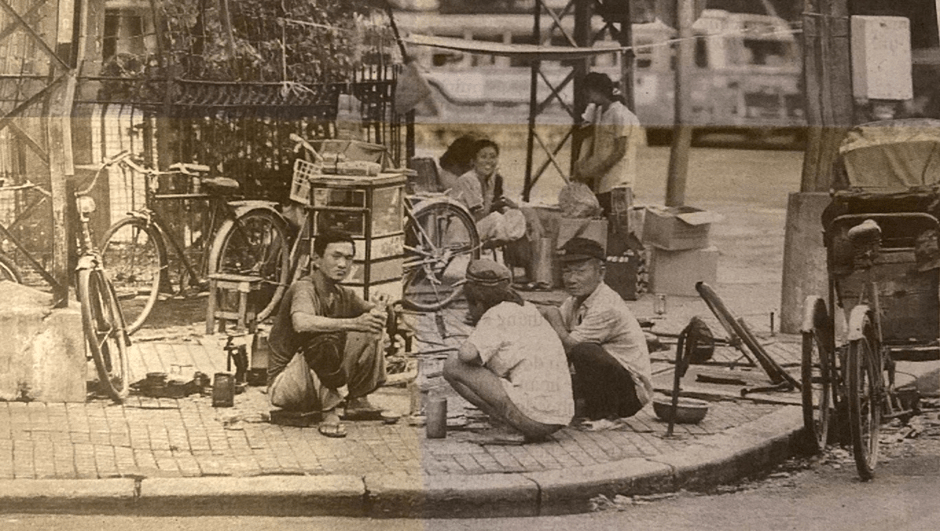

At the intersections and T-junctions of Sài Gòn, whether on wide boulevards or narrow alleys, street life is a form of freedom. These vendors may have little, but they are free—to work, to linger, to live life on their own terms.

They sell everything: food, drinks, snacks, they fix bicycles, sell general goods, newspapers—anything. Their stalls stretch across the footpaths like threads weaving a tapestry of everyday life.

To me, these street trades are a hallmark of urban living. Without them—without the working class buying and selling, or groups of teenagers sitting curb side sharing stories over iced coffee—Sài Gòn would feel empty, stripped of its soul.

The Sài Gòn of my youth wasn’t so crowded. Not like now, when millions surge through the streets, especially at day’s end, erasing the quiet existence of those who live and work at intersections, corners, and narrow lanes. In that blur, their presence becomes invisible. That is no longer a beautiful picture.

Perhaps this is inevitable. A city swollen with people becomes chaotic, frayed, restless—far from the calm Sài Gòn I once knew.

I left my hometown years ago. And each time I return, I’m overwhelmed by the ocean of motorbikes, the dense crowds, the street vendors now packed into every corner. It’s my city, and yet—somehow—not quite mine anymore.

I often tell my friends that in Chợ Lớn, most houses facing the main street have been turned into shops, eateries, or stalls. People say, “Nhà mặt tiền là tiền mặt”—street-front homes are cash in hand. If you don’t run a business there, you rent it out. There’s a long list of those waiting to do so.

Own a house on a main street, and you don’t really have to work. Rent alone will carry you.

It’s not just the main streets anymore. Even houses in back alleys are sought after for shopfronts. Sài Gòn is a maze of lanes—too many to count. There’s no census that could keep up with the sheer number of shops now dotting the city.

This kind of street trading isn’t new. Even when I was young, people sold what they could just to get by. But now, it has taken the form of a sprawling informal economy.

Among these small trades are street vendors who arrive from across the country, carrying their goods in baskets, hoping to make a living. From the outside, it looks industrious, full of life. But viewed through an economic lens, it’s uncertain, and often without security or long-term meaning.

So— is this a happy story, or a sad one?

Perhaps it’s both.

But I still see beauty in this way of life—what Lý Lan so gently calls the “social life of people at the intersections.” Whether they truly live on the corners of busy roads or tucked into hidden laneways, they are woven into the rhythm of the city’s breath.

I often think back to a coffee cart in my own hometown, run by an old Chinese man. The memory comes to me like a dream—soft, vivid, and fading. He passed away long ago, but I remember his cart well. It reminds me of my friend’s coffee cart near Xóm Củi.

Around his cart, the old Chinese man placed three plastic-wrapped cardboard boxes, forming a long, neat table where customers could rest their cups. He opened at dawn and closed at dusk.

One day, I sat at his cart. I crossed my legs on the plastic stool, called for a coffee and a fried dough stick. I poured the rich, fragrant brew—thick with condensed milk—and dipped the dough into it slowly. We chatted, idly, about the moon, the stars, and other small things.

In that moment, I don’t think he saw me as a child, but simply as another customer. Or perhaps he was just glad for some company during the quiet hours. After making my coffee, he returned to his nylon chair, laid back, and spoke to me from there.

I asked him, “Why don’t you get your children to help out, so you can go home and rest?”

He replied, “They’re working. And this is my home.”

It reminded me of something Lý Lan once wrote: “When I said intersections aren’t homes, Mr. Su objected: ‘Why not? This is my home!’” It may sound funny. But it rings true.

The old Chinese man with his cart, Lý Lan’s Mr. Su selling second-hand clothes in Chợ Lớn, the countless workers balancing baskets along the footpaths—they live on the street, and they make it their home. From morning until night, sometimes into the early hours, they sell, rest, talk, and wait.

Lý Lan puts it this way:“Day after day, they surround the intersections and never feel crowded. Intersections have their flows—people coming from all directions, like a river. The water keeps moving. There is something calming about it, something that becomes routine, then habit, then maybe culture, maybe even philosophy.”

At the end of each day, the old Chinese man would gather his things. He’d use the plastic boxes to build a little enclosure—just like a makeshift shelter, a temporary house. I once delivered a bag of rice he had ordered, and I saw how modest his real home was: dim, lonely.

He lived with his wife. She smiled softly when she prayed. His wife passed. He lived alone. His son had married a Kinh woman, and they lived somewhere in Chợ Lớn, selling vegetables near Bình Tây Market. Occasionally, they brought the grandchildren to visit the old man.

Much later in life, I had my own small taste of life on the pavement. One morning, after teaching, my Vespa broke down. I rolled it to a corner, near an intersection, where there was someone who fixed motorbikes. The repair would take hours.

I bought bánh mì and lay down in a hammock strung between an electric pole and an old tamarind tree. At lunchtime, the mechanic’s wife brought him food, and they ate together.

We talked. I learned they had moved from a small country town to the city to work and rent a room. She washed dishes at a nearby restaurant. Their place was so small she couldn’t cook, so they mostly eat cơm bình dân for lunch. At night, she worked late and often ate and slept at the restaurant. He managed dinner on his own.

I don’t know how long he has lay in that hammock. I don’t know if their home was like that of the Chinese man I knew as a child.

Maybe I wasn’t familiar with that world along the crossroads of Sài Gòn. Maybe that’s why I always felt slightly uneasy with the idea of a street corner as home.

But for many, it is.